By Philippe Matthews

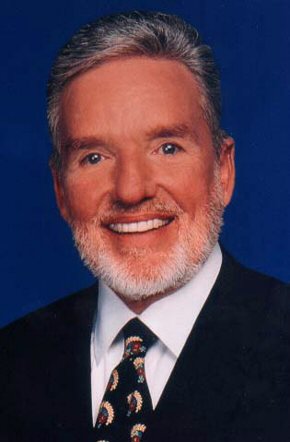

On June 29,1933, a man was born in Houston, Texas that would grow up and become one of the most influential psychologists of our time. His name is John Elliot Bradshaw and in the early to mid 1980’s he became a primary figure in the contemporary self-help movement particularly in the fields of family systems, co-dependency, and addictions and recovery.

He has touched and changed millions of lives through his best-selling books, sold-out workshops and seminars, and especially his widely acclaimed PBS television series on The Family, Homecoming, Creating Love, Eating Disorders, and his latest series on Family Secrets.

Bradshaw’s passion to help others he says came from the safety he felt in his childhood. “A lot of us in childhood have an innocence,” he shared. “The innocence is not that you don’t fail or miss the mark sometimes but it’s that you have a calling. It’s part of the poetic traditions and most of the spiritual traditions – they believe that each one of us is unique and each one of us has a calling. In my case, the thing that was so wonderful for me was family. I used to love to go my grandmothers. We used to go every Sunday and all the family would gather there. It was a wonderful time and kind of a metaphor of security – a base of warmth. Even though a lot of the people were not warm and nurturing, they were more shame based; there still was this metaphor that this was a place of security.”

But young Bradshaw lost his sense of safety and security when his parent’s marriage began crumbling right before his eyes. John laments, “I knew very early on that my mother and father’s marriage was in trouble. It was very clear that their marriage was disintegrating and I knew very early on that my father was sick — he was an alcoholic. He was a sweet loving man but he was totally irresponsible. When I was about thirteen they divorced and we moved ten times in fourteen years. We had to split up the family and live with relatives. My sister and I lived with my grandparents. My mother and I lived with my aunt and uncle. Then we lived with my dad’s mother who was a terrible alcoholic – that was a God-awful year — I have some real traumatic memories of that! I just grieved their divorce. I can remember at thirty years old being intoxicated having this fantasy that I was going to get them back together again – they had been divorced for seventeen years!”

The pain of divorce affects many children well into their adult lives, Bradshaw was not immune to this pain as the breakup of his parents still affects him to this day. “A couple of years ago, I saw a program on divorce and support groups for children and I went into abdominal sobbing by the end of that program because what I suddenly realized was that my mother announced one morning that they were getting a divorce. It was never spoken of again. Our life and love had been destroyed. There was never any closure.”

The Genetic Alcoholic and The Shame Game

The family supported John’s mother more than the grieving children, John soon became what he calls an “emotional husband.” He says, “I would take care of pain. I remember sitting for hours outside of her room when she was just crying in there. I was yelling, ‘what’s the matter?’ it was crazy! I had a little chair and I sat by her door because my job was to take care of her pain, which has really affected me in my life in terms of relationships and intimacy. I was the hero of the family. I was the one that made straight A’s and was the president of every class and I gave the family a sense of dignity. But, that’s a very rigid role. In other words when you have to be the hero you have to give up certain things. You can’t be vulnerable, there’s certain emotions you can’t have. So, by the time I hit thirteen or fourteen I begun to drink and clearly was a genetic alcoholic.”

To inoculate himself from the pain of being the emotional crutch in the family, the teenage Bradshaw continued drinking heavily. He recalls having blackouts and long periods of amnesia during his drinking spells. “You wake up in the morning and don’t remember anything after eight o’clock the previous night! I knew very early on there was something very serious about this. I vowed to quit over and over again – went through periods of quitting but I came back to alcohol because I felt so shame based, so inadequate. One of the things that was very dominant in my family was shame. My mother could shame you on the in-breath! She just didn’t understand what shame was and never did. Shame is a sudden rupture of your experience. You feel helpless in the moment and you can imagine that happening when you’re two or four years old.”

Bradshaw’s shame grew deeper and deeper as he continued to explain. “I quickly began to feel inadequate. My family was poor, we never had a car. We use to go to church on Sunday on the bus right on the outskirts of the wealthiest area of Houston and I just felt ashamed. I’d get off the bus five blocks early so nobody would see me riding the bus. Even in my life now, anytime I go into a place where there’s any semblance of well-to-do-ness, I feel a twinge of guilt like I don’t belong here.” Bradshaw has sold more than eight million books and has earned millions in royalties but still finds himself wondering if he’s deserving of it all. The wound of shame, although closed, the scar remains in his dominant belief system. “The wound is still there and my position is you never get over shame. Shame is like trauma. It’s post traumatic stress, it’s violent and when your shame has been internalized it means that it has been chronic. It isn’t just being beaten or being incest that creates the post traumatic disorder of chronic shame, its habitual measuring. No matter what you do it’s never good enough.”

While Bradshaw was in the seventh grade he remembered the shame of being poor as one of his classmates got a car and how lavish he lived. “I can remember spending the night at his house and they had maids. That to me was just extraordinary and they had this beautiful house. My mom went to work and stayed at the same job for forty years and her end pay was $2.42 an hour. She worked at Foley’s department store.”

The Priesthood, Alcohol & Sexual Abuse

At seventeen, Bradshaw went into the priesthood to find solace and vindication from the shame that was developed in his childhood. Unfortunately, the baggage he thought would be left behind was waiting for him in his next experience. John recalled, “My alcoholism increased but I kept hearing the voices of the nuns from my childhood and then I had a priest who was abusing me sexually but I didn’t understand that he was abusing me sexually. He kept talking about intimate things, tried to touch me on several occasions. Would hug me and tell me he loved me and I got straight A’s from him and I was running with this wild group of guys and we were drinking and whoring. I thought I was manipulating him but here I was a kid that had no father and I would gravitate to guys who came from broken homes with no fathers. My mother had a sexual disorder – meaning she had been violated by her grandfather and she never dealt with it and when she divorced my father she was about thirty one, she died at age eighty two and never had a date with a man!”

Bradshaw also remembers when he asked his mother in later years the question, why did you choose not to go on a date with a man after divorcing his father; the answer he received was startling. “My mother said because she was too sexual! You would think of her as very prudish but she was also unconsciously seductive and I was her surrogate husband. She would have me fix her brazier or, help her take off her girdle. I can remember too late in my life her coming in and using the toilet while I was taking a bath. At the time I didn’t understand because it was too much – you can violate a child sexually by over stimulating them by not having good boundaries. Later in life, I talked to my mother about this and she did not defend herself. I feel there was never any malice in this, it’s what I call covert incest.”

The emotional dysfunction that occurred from these young years of Bradshaw with his mother also became one of the catalysts that drove him to the monastery. The series of childhood events that stripped away his innocence became the very foundation that satiated his dual passion. Bradshaw explains, “One [passion] was the soul level in which I really wanted to care for people for the family of man and woman. I knew that I was willing to give up my sexuality and family life in order to be a soldier for Christ. I married Holy Mother Church and became celibate for life. Number two was the psychological dynamic that I was continuing to marry my mother and commit my life to Holy Mother Church and never have sex because that would be divorcing mother.”

The Good/Evil Fight

John explained that his drinking became more profound. “The chemical itself began to get me out of control I could not be in that seminary and hide that I had a serious problem.” One night, John got drunk and went screaming down the hallways of the seminary and calling the superior filthy names. With humor and lament, John recalled, “I knew the seminary needed reformation and so did a lot of other guys. We knew there was something wrong with celibacy and there was something wrong with the way they were teaching us.” One of the ironies that Bradshaw discovered years later was that an inordinate number of men who were Catholic priests in that community died before they were forty five years old. “I talked to other guys in the seminary and it was like an, ‘ah ha!’ There was a part of those men that had reached such a level of despair that they wanted to leave but couldn’t leave. It’s like you wanted to die but you’re afraid to die. It’s one thing to be in a prison camp. It’s another thing to be a soldier for Christ and feel trapped.”

John is thoroughly convinced that his drinking became the pathology of his soul. “It was a part of me screaming out that I thirst and there’s an emptiness in me.” Ironically, leaving the seminary in 1963 increased his addiction to alcohol and took him to the threshold. He literally got into a spiritual fight with his deep-seated, negative self-image. “I was teaching at the university of St. Thomas. Their idea of helping was sending me to teach a hundred and eighty students philosophy, theology and English. By Christmas that year I had disintegrated. I was drinking, I was taking about three hundred milligrams of Librium everyday and I was still voted as teacher of the year, which shows you a person can have an addiction and still function. I swear I don’t know how I made it.” By this time, Bradshaw was thirty-one years old and the superior of St. Thomas University only gave him four hundred dollars upon his leaving the church. He had no clothes and no place to live. “I didn’t have a suit of clothes and I couldn’t drive a car!” Bradshaw remembered. “I stumbled around and my mother’s best friend came and got me one day and took me to the Houston Council of Alcoholism and introduced me to a guy named Frances Yeager who was a professor at the University of Houston.”

John is thoroughly convinced that his drinking became the pathology of his soul. “It was a part of me screaming out that I thirst and there’s an emptiness in me.” Ironically, leaving the seminary in 1963 increased his addiction to alcohol and took him to the threshold. He literally got into a spiritual fight with his deep-seated, negative self-image. “I was teaching at the university of St. Thomas. Their idea of helping was sending me to teach a hundred and eighty students philosophy, theology and English. By Christmas that year I had disintegrated. I was drinking, I was taking about three hundred milligrams of Librium everyday and I was still voted as teacher of the year, which shows you a person can have an addiction and still function. I swear I don’t know how I made it.” By this time, Bradshaw was thirty-one years old and the superior of St. Thomas University only gave him four hundred dollars upon his leaving the church. He had no clothes and no place to live. “I didn’t have a suit of clothes and I couldn’t drive a car!” Bradshaw remembered. “I stumbled around and my mother’s best friend came and got me one day and took me to the Houston Council of Alcoholism and introduced me to a guy named Frances Yeager who was a professor at the University of Houston.”

Bradshaw’s internal yearning for help and redemption took him beyond the threshold of denial to the point of delusional. “Denial is real denial, you know you’re denying,” explains Bradshaw. “Delusion is sincere denial – you don’t know you’re in denial. You think it’s true.” When Frances Yeager and some of the other people in the twelve-step program confronted him, he began making progress with his liquid demon but after forty days of being sober he got drunk again, got into a fight at a bar and ended up in a paddy wagon. “My violence would come out;” John recalled. “This good guy people pleasing part of me. This caretaking, giving up my self to take care of everybody else’s pain part of me led me to believe you should beware of extremely nice people because there is a shadow side to them and when it comes out it’s awful! So, when my shadow came out it came out in this violent rage and I went through every friend I had. I remember standing in a shoddy bar at a telephone calling every single person I knew and asking him or her to join me in an evening of drinking and not one single person came. That was my beginning awareness of the bottom.”

Rock Bottom & The Rocky Road Back

On December 11, 1965, Bradshaw ended up in the Austin State Hospital. He continues to celebrate that day; because that was the day he took his last drink! “I was there six days and I knew this was the bottom. I was thirty-two years old and I knew I would do this again. I knew my life was unmanageable and drinking was the cause of it. I remember standing there saying to myself that I was going to go back and follow that twelve step program like you follow a doctors prescription. I would take those steps as if it were a divine command. I went to two or three meetings a day and the first five years I averaged two meetings per day and became a very active member of twelve step work and helping others.” During Bradshaw’s commitment to conquer his addiction, he got married, was expecting a baby and was teaching at a high school before losing his job. “Here I was with a new wife who was pregnant with no money, no job and that’s when I began to create my life. I began to do workshops and create courses at a local church.” Not long after making his commitment to help others help themselves, Bradshaw was in demand as a counselor, teacher, public speaker and corporate consultant.

In the early 1980’s he produced The Eight Stages of Man, an eight-part series for PBS. Over the years, he has helped raise over $12,000,000 for the Public Broadcasting System through his production ventures. In 1985 with the airing of the ten-part PBS series, Bradshaw: On The Family, John became a public television phenomenon. Throughout the 1980’s and 1990’s, his television productions including Where Are You Father, Healing the Shame That Binds You, Adult Children of Dysfunctional Families, Surviving Divorce, Bradshaw On: Homecoming (Reclaiming and Championing Your Inner Child), Creating Love, Eating Disorders and Bradshaw On: Family Secrets gained huge audiences for PBS across the country.

From 1969 to 1988, John had a thriving counseling practice. He counseled over 800 couples. He served on the Board of Directors and as President of the Palmer Drug Abuse Program from 1981-1988. He was the National Director of the Life-Plus Co-Dependency Treatment Center from 1987-1990. John was the Founder and National Director of the John Bradshaw Center at Ingleside Hospital in Los Angeles from 1990-1993.

In 1991, John was nominated for an Emmy for Outstanding Talk Show Host for his series Bradshaw: On Homecoming. In 1996, John was the host of the acclaimed nationally syndicated television talk show The Bradshaw Difference produced by MGM. John has appeared on Oprah as well as hundreds of other television and radio talk shows.

Bradshaw continues to travel doing lectures and workshops throughout the world. John Bradshaw resides in Houston, Texas and spends time writing and fishing at his Texas and Montana ranches.

Philippe Matthews Show Guru Advice, Author Reviews, Tech Reviews, Entertainment News

Philippe Matthews Show Guru Advice, Author Reviews, Tech Reviews, Entertainment News